archive

Nigel Ayers on electronic music, Iraq , psychogeography and Bodmin Moor

(2007 Interview from art cornwall)

Trained as a visual artist, Nigel has worked as a musician and composer for more than 20 years and has made hundreds of recordings both in his own name and as 'Nocturnal Emissions'. He now lives in Lostwithiel, Cornwall.

Though you are probably best known for your music, I understand from your CV that you were in the 'New Contemporaries' show in 1977. Were you a visual visual artist then, or were you already into sound and electronic music at that stage?

Mostly visual back then, though I’d done quite a lot of experimenting with soundtracks for films and slide shows.

Where did you go to art college, what was it like, and what were you into art-wise at that stage?

Because grants were available, I think art school attracted a wider (and often crazier) cross section of the population back in the old days.

Straight out of school in the early 70s I did an Art & Design Foundation course at Chesterfield for two years. I enjoyed it because each study block lasted only 3 weeks and then you were doing something different. I never learned to draw or paint, but looking back I could do that kind of thing anyway. I gravitated towards technology – derived bizarreness, assemblage art and experimental film, anything radical that went beep and had flashing lights, there was also a strong Fortean side to what I did, which has persisted.

Chesterfield had a good light-sound studio where I experimented with quadraphonic sound and multiple slide presentations. I’d always try and get something subversive or at least something kinky looking in there. Something to mess with people’s heads.

New Contemporaries was a national show for students’ work. At the time I got showed I was nominally doing a BA in Sculpture in Bath , but the pieces I entered weren’t really sculpture. One floor piece was made up of dozens of plastic bags sellotaped together into a blocky human outline. Inside these were a year’s worth of personal mail, two people’s

hair and tiny fragments from a super 8 film.

The other piece was made up of multi-coloured screen prints which reproduced text and images from old children’s encyclopaedias, Sunday magazines, the Queen and a little bit of pornography. What I did was multi-media assemblage, using the material that was about me and playing with the ideas of knowledge, of display and really taking the piss out of serious art. A lot of what I did were complex and time-based environmental pieces that you walked into, it wasn’t called installation art in those days, I was attempting some sort of total art, something very experimental.

1977 was the Silver Jubilee year which was, for many, the year of punk. Around about that time, as I recall, a number of other genres emerged including e.g.'industrial music', which was often electronic, linked to Brian Eno, and a kind of precursor to ambient house.

Yes, this was very much a crossover, a break down of barriers: anti-art, non-music, so it attracted a lot of artschool types.

The beauty of punk back then was it wasn’t an homogenised scene. Reggae, especially dub, got played a lot. The DIY idea really got going and for about 10 years it was quite possible to self-release very non- commercial and experimental records and there were independent distribution channels and a small but keen world wide audience who would buy them. This also meant that there were channels open for self published zines, too. So, this seemed a far more attractive option than chasing up galleries, or applying for arts council grants, or getting into teaching, whatever artists did back then.

How did that relate to the music industry as such?

There is a commercial music scene producing entertainment to brainwash the masses and there is a non-commercial scene with different priorities. Many people in the underground scene were very career-driven and were using it as a leg-up into a commercial world, but we live in a capitalist society and you have to get an income from somewhere.

The trick is to find your way through a corrupt system while preserving a bit of integrity.

Scritti Politti - amongst others - went on an interesting journey from one music world to the other did n't they?

What were you listening to at the time?

I have always been listening out for new sounds, what I liked about John Peel was the variety of material he would broadcast. I also got deeply into traditional music, there was an ethnographic section in my local music library which I would always be digging into. When I lived in Brixton, I’d often end up in late-night shebeens where I’d absorb a lot

of dub as well as the other intoxicants on offer. The reason I got into electronic-based music is I’m not a great musician, but I like to listen. So if I can set up a machine to play what I want to hear, that’s great.

So how did Nocturnal Emissions form?

Out of boredom and frustration mostly. It grew from improvisation sessions a group of between two and four of us did in this house we squatted in south London . I wouldn’t say these were very good, but they were unusual and I thought somebody somewhere might find them interesting.

I copied up cassettes with photocopy inserts and sold small batches of to Rough Trade. I sent them out to anyone I could think of. This was audio, not visual art, but I sent them out to mail art people. One of the copies I sold to Rough Trade found its way to Japan where Masimo Akita of Merzbow reviewed it for a magazine.

With no business training whatever we saved up some cash from agency work and made our first LP and began playing live. As we never made any attempt to get popular, I made a point of recording all our live shows and releasing them on cassette to give a sense of occasion. Our timing was impeccable, one of the first gigs we did was in what the called the “front line” in Brixton while a major riot was going on outside. We had strong ideas about music as a device of social control and experimented with infra and ultra-sound (which made for problems cutting the first LP) and tape cut-ups, (the sampler wasn’t invented back then) information overload, and subliminals. An overall very paranoic and manic kind of sound. Our performance were live sound collages, as we pieced together more equipment we used super 8, 16mm film cut-ups and slides and later video projections along with the performance. We attracted an underground following in Germany etc.

Was Nocturnal Emissions a group or a collective, or was it always just you recording and performing alone?

For a while two of us made a full-time living from this and we worked with up to five or six members, but I was always at the core of it. It’s a group identity because I don’t believe in a consistent individual identity. I saw the records and cassettes as “multiples” in a Fluxus sense. We produced collages and text pieces and manifestoes, using photocopy as that was the most direct and accessible media.

We produced collages and text pieces & manifestos which we sent out to anyone who showed any interest. Back when we started there was no outlet for experimental/personal cinema but the context of as live music performance we could screen the material in unconventional venues. I’m a firm believer in a breakdown in categories and I simply just don’t do pure art. There was no You Tube.

I worked with juxtaposition and collage, the idea is deprogramming. It was important not to get bogged down in genre, but to use any means necessary.

Am I right that you toured the world, and what were the highlights of that period?

Not the entire world, most of Europe and some Eastern cities in North America is all. We got loads of US publicity and nationally syndicated radio coverage from just doing a few very small concerts. I think I could easily have made a living there, but I wouldn’t want to live there. Lots of odd things happened - at one stage we were approached by Motown!

Did you get to meet or work with many interesting people?

Plenty of interesting people. Maybe not many famous people.

I’d met Captain Beefheart before I got started on this lark, which is going one better than Bono who only talked to him on the phone. Our videos were published in the US by some of William Burroughs’ crew. We worked with Geff Ruston aka John Balance of Coil really early on. Graeme Revell of SPK who is now a Hollywood composer – Shwarzenegger films etc, and Brian Williams who is also doing soundtrack work there.

Tibet , Stapleton, Touch, Neubauten, Vittore Baroni, Max Headroom. We recorded with the guy who does the breakbeats for the KLF whose name I’ve forget. Of group members, my brother Danny who did techy stuff has been the most popular Danny in Google searches for a couple of years now, Stanza who played drums for us is now a very productive new media artist, Fiona Harrold who did vocals is now a “self-improvement” writer.

Did you maintain an interest in visual art eg through video or graphic design during this period?

Yes we did our own packaging designs and made videos. We put out mini collage radio programmes on cassette.

What sort of thing were you doing? How did it look?

We made things that were very simple and direct, we were keen that design didn’t get in the way of the substance of our work. We stuck to very basic typography and we’d use messy cut n paste - or simple classical layouts with a conceptual art look.

Our videos, funnily enough, though the weren’t intended as art, were screened at the Tate, ICA and the Arts Council included them in one of the first big tours of video art. The were very different to the New Romantic type work being produced at that time by the likes of Cerith Wyn Evans and Derek Jarman. We pioneered an approach that was very DIY and rough at the edges, as we had no access to professional studio equipment - we were working with domestic video using crash edits. Everything was so much harder to do back then.

When did you move to Cornwall , was there any reason for coming here, and how has is worked out for you?

I moved here in 1993, I always wanted to live here and I thought if David Kemp, Paul Spooner and the Aphex Twin were down here then it must be conducive. I love the environment and the people here, but.....it can be hard sometimes!!.... The logistics are terrible. On the plus side, the net has helped a lot.

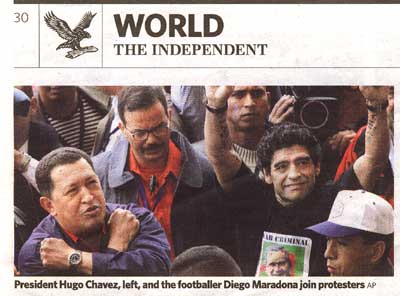

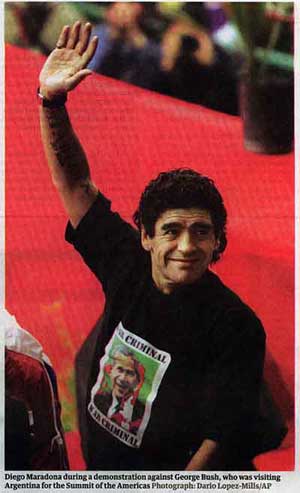

In 2003 I understand you designed placards and T-shirts denouncing Tony Blair and George Bush as war criminals. These have subsequently appeared in anti-war demos all over the world. Do you want to expand on this project a little more?

It’s amazing how images spread once you get them on the web. I was very much involved with local Cornish groups opposing the invasion of Iraq . Though I’ve been on loads of demos I’ve never been on so many as I did that year. Weapons inspection at RAF St Mawgan was one of the highlights, as well as kids walking out of school in protest against the war.

Getting involved in that kind of thing makes your can use your art skills in a way that is far more meaningful. It great when things you’ve made for a demo shows up on the TV news, it’s a more interesting (and easier) way of getting your work seen than showing it to a ready-made audience in a gallery. Though of course it comes through the filter of media distortion.

What you need for demos is plenty of eye-catching placards, so that was one of the things I busied myself with. I did a design of George Bush War Criminal and made these available for free download so that anyone in the world could use it, 2 years later opened my newspaper to find a photo of Diego Maradona wearing it on a T-Shirt!!

This was on the front cover of newspapers all around the world, including the US , so I like to think that Bush might have seen it. It’s good to get focussed on action even though you know, after years of campaigning, that politicians tend to respond to big business and the corporate interests behind the press rather than people in the street.

Incredible. There's something amazing about the idea that an artist in Cornwall can make an image that can travel so directly across international boundaries and time-lines. Have you used art in such a political way before?

I think politics is always in my art somewhere, though it’s not always so obviously propagandist.

The point of doing art is to cut through the way these activities are separated from everyday life. What I produce is a result of all of that, and trying to make some kind of sense of it.

You say politics is always in your art, but can music ever be truly political?

Sometimes it’s very deliberate, sometimes it’s just a result of circumstances. I do see what I do as part of a cultural campaign, and I do think (like old feminists) that the personal has a political dimension. Because I can’t help questioning the nature of reality and what it means to be human in what I do.

The idea of ‘art’ has only been around 200 years and is a very reactionary class-based idea. However, it can also be a way of establishing moments of possibility, or suggestions of potential that upset the profit-orientated system. I have noticed that most of my output is marked by a blurring of category boundaries, production by any means necessary, use of open networks for distribution. It’s different from entertainment.

I’m interested in the history of people who have challenged this art/life thing and attempted to become more fully human through doing their art (whatever form it takes). I think that all art is political, whether intentionally so or not, the way its organised, produced and consumed can be a very effective (if often very insignificant) way of upsetting consensus reality. It may be something to do with the self-organising side of it.

Music is often more political than art, as it brings people together across barriers of language, race and background. I don’t think art has to be directly propagandist to be political. Totalitarian regimes are threatened by art, and seek to suppress it. Economically liberal regimes turn artists into just another commodity.

You have worked with Stewart Home on projects in the past. Stewart is known as a writer and an expert on Situationism, amongst other things (I am a proud owner of his book The Assault on Culture'). How do you know him?

I can’t quite remember, think he must have been a friend of a friend in the early 80s, I know copies of ‘Smile’ used to turn up in the post.

A magazine he founded in the 80s, right?

Yes. I’ve been in regular contact with Stewart for over 20 years now, since we helped organise the Festival of Plagiarism in London . When he published ’Assault on Culture’ it was uncannily similar to something I’d written myself for an art school essay, but never published.

So are you sympathetic to the ideas of the Situationists?

This is a tricky one, as I am very aware that the SI are often invoked these days to promote very bland and unimaginative art. Art that seems to reinforce a very bureaucratic and conformist mentality. In the 70s and 80s the SI were better known in the margins of ultra-leftist politics than in art, and you’d be more likely to come across their work in an anarchist bookshop than a library.

Nowadays they seem to be a hit with academics. It’s very fashionable in art circles to invoke the Situationists without having the slightest idea of what they were on about, or their historical context in Paris in the mid 20th century.

It’s little wonder, as their writing is hard to read, and badly translated so it can often mean whatever you want it to mean. There were very different strands of opinion within the S.I.. I don’t particularly like Debord, but he had moments of lucidity: the idea of detournement, that is taking an everyday element of popular culture and turning it around to find its subversive potential. He was also quite clear about recuperation, where a subversive idea is turned around to bolster the ideology of the dominant system. The dominant system is now using reference to the S.I. to promote a boring kind of art, (reflecting the changes from a manufacturing to a service economy).

The best thing about the SI was they were very critical of the body of ideas they were surrounded with. Not so much art as commodity, but human life as a commodity and acting as a fully functioning four dimensional human being. They were also very clear about how entertainment is used for social control.

It’s not that they were artless, but they opposed art that commodified everyday life.

Can psychogeography (a situationist idea) only be applied in an urban setting, as this has how it has tended to be used? To me it would seem interesting to think through what it might mean in a rural context...

Psychogeography emerged as an urban phenomenon as a critique of what modernist town planners were doing to a city environments, specifically European cities in the 1950s.

I think what the psychogeo missed was engaging with the binary oppositions of urban and rural spaces, and the meaning of those oppositions. That is, the impact of capitalism on all social spaces, the way enclosure and ownership of the natural environment and its resources is a very political issue, worldwide. And that access to open space is critical.

But what interests me is how rural space is perceived as negative space, the space between places. Hence the metaphor of space travel and a geomantic system borrowed from dowsing and mediumistic art, overlaid with gritty realism. I think artists like Richard Long concentrated on a romanticised timelessness, but the rural landscape is not timeless. We see it through modern camera lenses. It contains traces of earlier occupancy which propels us backwards and forwards in time.

In a very simple form psychogeo is an approach to the urban environment which seeks to engage with “magical” experience, a kind of dreamtime, in the sense that it breaks through the norms of capitalist exploitation of space. The idea of rambling, of free association taken off the page and into the real world, emerged as a reaction to the homogenisation of urban spaces. I’m a rural dweller who engages with information systems.

The idea of autonomous rambling emerged as a reaction to industrialisation.

I find its good to explore what’s perceived as non-space by Debord. I like the way abstract information systems can connect in new ways with physical objects. Not just social networking, but physical interaction with the material world.

More recently you have been making interactive sculptures and installations including the 'Desiring Machines' (pictures above) - the title a reference to Deleuze and Guattari…

It is presently difficult to escape the influence of Deleuze and Guattari on new media art theory. In Anti-Oedipus, Deleuze and Guattari identify ‘bricolage’ as the characteristic of schizophrenic production. The authors created their book by a bricolage process, yet as a philosopher and psychoanalyst they were not themselves diagnosed as being mentally ill. What they were doing was to apply surrealist literary techniques such as bricolage to the field of philosophy.

In contrast to Deleuze and Guattari, I feel it is very wrong to medicalise an effective method of production. The fear of appearing mentally ill acts as a powerful means of social repression and so may often deter people from using bricolage techniques.

So much art is about the creation of desire, the manipulation of desire (and fear) is what advertising is all about. D& G suggest that the hedonistic urges of humans as ‘desiring machines’ can actually have liberatory potential. The idea with these machines is they not only use a system of conventional sensors to produce sound and light, they also contain elements drawn from fringe sciences, like radionics, Ouija boards, and dianetics, and you can never tell what elements of human stimulus they are responding to, whether it’s sensory or extra-sensory.

They are partly creating sound and light patterns by themselves as partly reacting to quite ordinary measurable stimulus such as light and heat etc and operate as complex systems, similar to very simple forms of organic life. I saw this as potential art form, as it moves between electronics and something on the edges of belief.

And a sculpture called 'The Planetarium must be built' (below right) based on your book 'Bodmin Moor Zodiac'. Can you explain the Bodmin Moor Zodiac project?

It’s an in-depth psychogeographical investigation of the imaginative potential of a rural space. Its something that hasn’t been done before.

And I’ve been exploring different ways of presenting the material. In The Planetarium, I used a restricted space that it was impossible to enter, enclosed by a silver dome and full of consumer electronics, used in a exaggerated way to emphasize their illusion-producingness.

In shamanic terms, the rural space is an Otherworld, and our contact with the Otherworld gives us something to bring back into everyday experience. The moor exists as a kind of negative space as opposed to urban space and it also necessitates a borrowing of metaphors from space travel and psychic investigation.

Its sounds like a fascinating project that probably deserves a separate interview or feature at some point...perhaps I can get back to you on that one...

go to www.nigelayers.com for more info

2007 Interview from art cornwall